I analysed 600,628 COP27 Tweets. Here’s what I found

Min Ruan, DPhil student, Oxford Smith School

From 6 to 18 November 2022, the 27th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27) in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, sent climate change action back to the negotiation table and ended with an agreement to establish a “loss and damage” fund. Even though the UNFCCC called it a “breakthrough”, we know that much is still in the air. And there were failures in other areas - As COP27 attendee and Smith School researcher Brian O’Callaghan stated: “… so far as mitigation is concerned, COP27 was a lame duck. The fossil fuel lobby very clearly influenced language to ensure that there was no progress from Glasgow on phasing out fossil fuels.”

But what did the public think? As a full-time DPhil student at the Smith School, my research focuses on corporate sustainability strategies and investors' responses to climate risks.

As COP27 approached, I became interested in what we can learn about public opinion on the conference from Twitter.

So, driven by curiosity - and a longheld fascination with data - I scraped 600,628 unique tweets using more than 60 languages that included “COP27” between 23 October and 18 November. Below is a summary of what I uncovered.

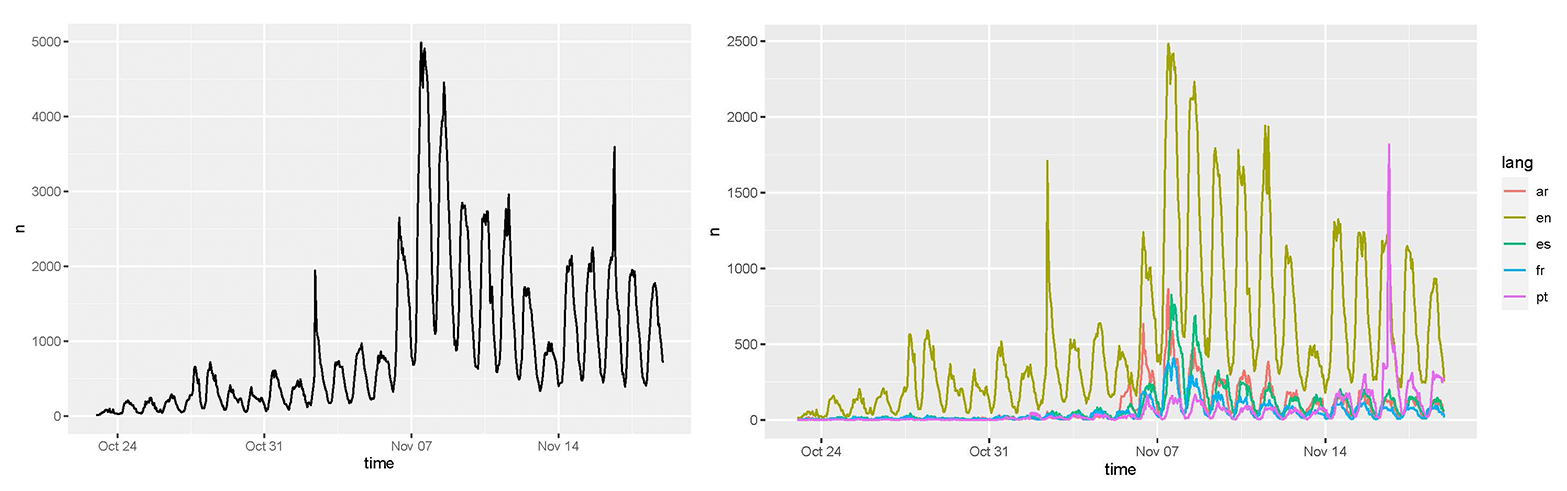

Visibility of COP27 on Twitter

27 is regarded as a lucky number by some. The timing of COP27 was not so lucky. It coincided with fierce US midterm elections (Nov 8) and the G20 summit in Bali (Nov 15-16).

Figure 1 shows the visibility of COP27 on Twitter. Before the opening ceremony, the number of tweets gradually grew and peaked at 5000/hour on November 7 (Monday), the first day of COP27. Then, it started to decline, especially on weekends.

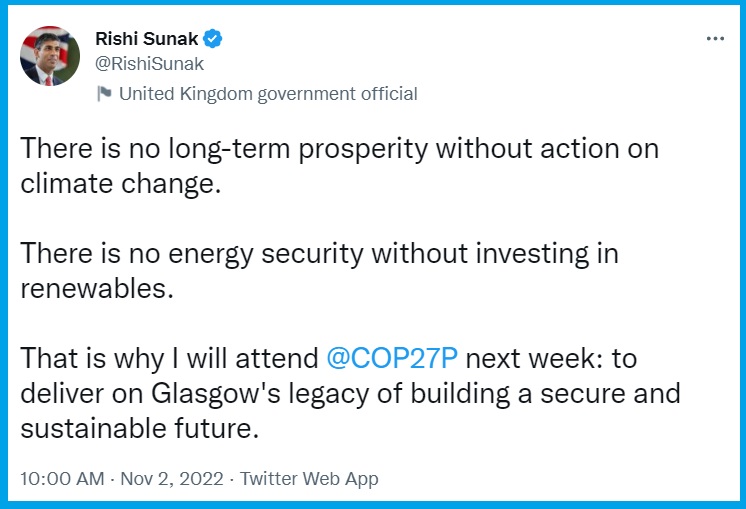

Curously, “COP27” tweets were irregularly peaking on November 2 and November 16. On the 2nd November, the new British Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, who previously decided not to attend COP27, tweeted:

On 16 November, the new Brazilian president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, attended the COP27 summit and huge crowds gathered to watch his speech in Egypt. “We must stop this rush to the abyss. There is no climate security for the world without a protected Amazon,” Lula promised. “We will do whatever it takes to have zero deforestation and the degradation of our biomes.” Again, the Twittersphere reacted with interest.

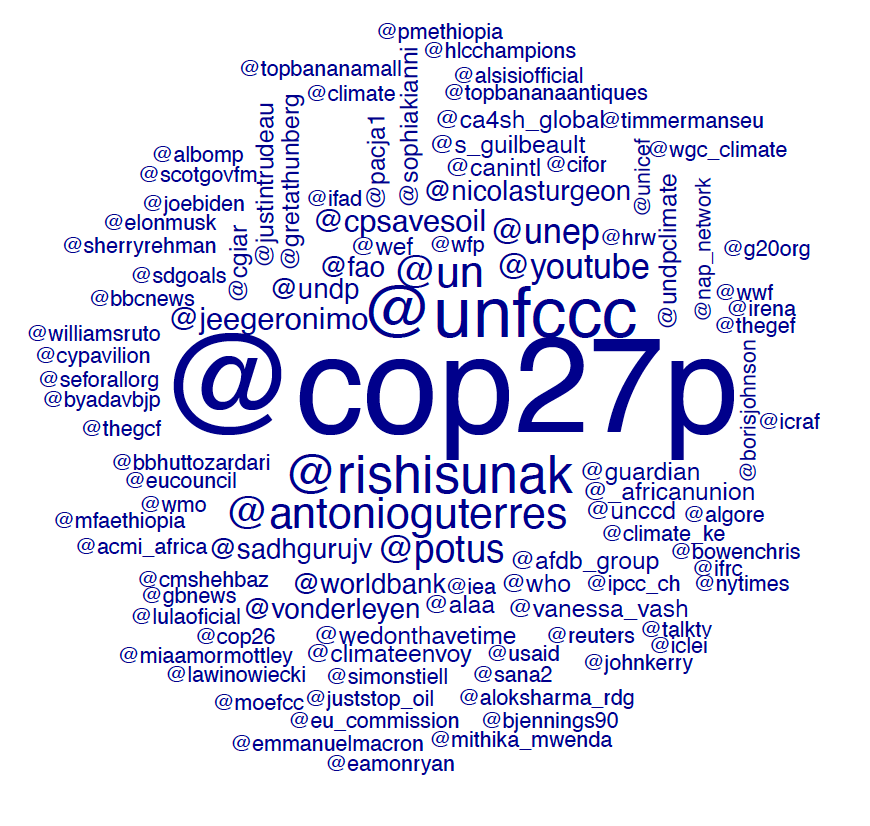

It is worth noting that these peaks were both due to newly appointed world leaders. The username cloud in Figure 2 further shows that the official accounts of COP27, United Nation organizations, politicians, and climate activists were in the spotlight and received much of the attention during the conference.

This perhaps demonstrates the importance of leadership to the public who are concerned about the climate crisis. As Dr Laurence Wainwright wrote in the Financial Times: “In times of unprecedented uncertainty, volatility and chaos, humans seek reassurance in two ways: clinging to what is known and stable, and the perception that something is being done to address the cause of the problem.”

On Twitter, COP27 negativity spread faster and further than optimism

Negative tweets won the highest retweets and the highest likes. A tweet, posted by @DiEM_25 on November 7, received 31,892 retweets, 3,121 quotes, and 90,919 likes:

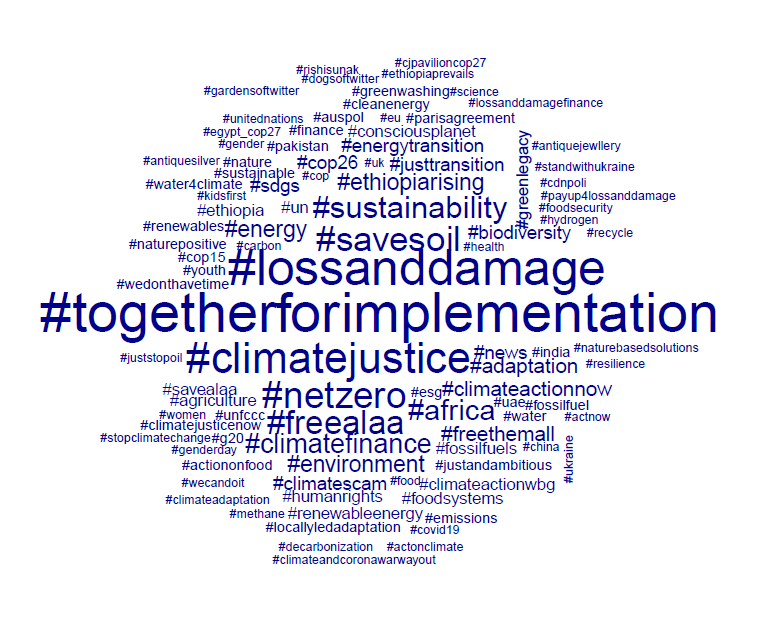

The hashtag word cloud in Figure 3 shows more. Besides the climate-related themes (#climatejustice, #finance, #adaptation, # biodiversity, #energytransition, etc.), the human rights themes stand out (#humanrights, #freealaa, #savealaa). Greta Thunberg disapproved Egypt’s human rights record and denounced the conference as an opportunity for “greenwashing, lying and cheating.”

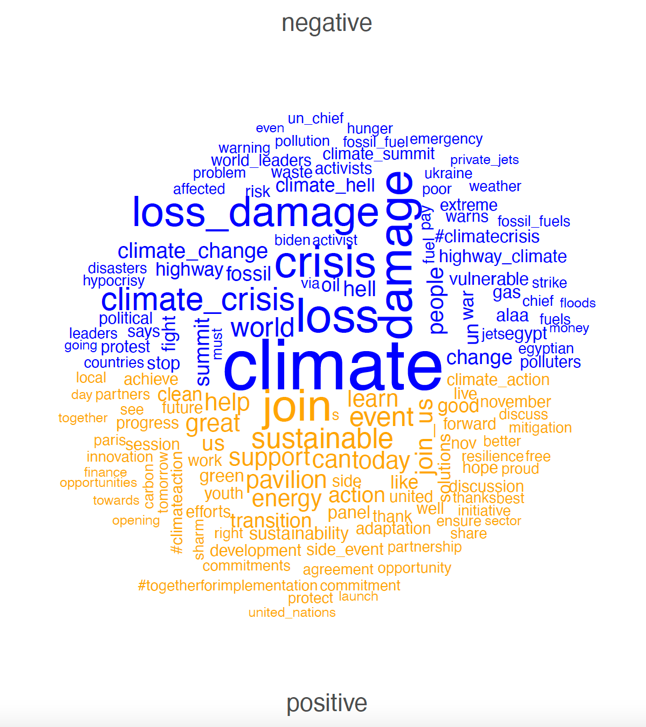

The sentiment comparison cloud in Figure 4 shows that people worried about climate disasters (hurricanes, heat waves, floods, droughts, and storms), Russia-Ukraine conflicts, intensive use of fossil fuels, climate scam and greenwashing on Twitter. António Guterres tweeted on November 7: “I have just warned global leaders at #COP27: We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot on the accelerator. Our planet is fast approaching tipping points that will make climate chaos irreversible. We need urgent #ClimateAction.”

What can we learn from Twitter data?

Firstly, timing is important – holding an event during the US midterms meant COP27 was always going to be battling for people’s attention, particularly in the U.S.

Secondly, the commitments of world leaders, particularly new ones, to attend the conference really do matter. Prime Minster Sunak’s COP27 speech may not have captured people’s attention, but his decision to attend certainly did.

From a reputational stand point, the COP format took a battering over the course of the event. From the selection of host (Egypt: human right issues) and sponsor (Coca cola: large plastic polluter and private jets), to problems with logistics and catering, a number of issues could be seen to distract Twitter user’s attention from the core issue: how the world will respond to climate change.

However, there is only so much we can learn from one social media platform. Indeed, a handful of academic literature proves the existence of echo chambers and growing polarisation on social media. Public opinions may be influenced by mainstream media, political propaganda, and many other factors. Last but not least, the accuracy of distinguishing real persons and bots is fraught with difficulties.

This all means it’s impossible to draw strong conclusions about public opinion from Twitter alone. But as I continue my DPhil at the Smith School, I am keen to delve further into the relationship between social media and climate change policy making.