Will Labour’s New Fiscal Rules Deliver Better Investments in Net Zero?

Dr Anupama Sen & Professor Sam Fankhauser

The Government’s planned changes to fiscal borrowing rules – reported to unlock over £50 billion in additional capital investment - could have a significant impact on the speed and scale of the UK’s green transition.

The current rule requires Public Sector Net Debt (PSND), to fall in a five-year period. The Government’s new proposal shifts the metric from PSND to Public Sector Net Financial Liabilities (PSNFL). The PSND calculation only nets off liquid assets (e.g. currency and deposits) from the debt calculation, while PSNFL also nets off illiquid financial assets (i.e. assets on which the Government expects a future return; e.g. student loans)[1]. PSNFL is therefore a broader measure of debt, one which allows space in the fiscal rules for the government to make investments that may not be immediately liquid, but would pay off in the long term. Estimates suggest that the rule change could in theory allow for borrowing of up to roughly £50 billion a year by the end of the decade while still adhering to the fiscal rules. This will give the chancellor significantly more room to maneuver, and balance investment needs across several competing imperatives, including enabling the UK to meet its Net Zero targets.

The change is good news for net zero investment - the shift in rules explicitly enables more public capital investment which will be crucial to funding or catalysing funding for green infrastructure. It is clear from Smith School research that low carbon technologies generate savings in the medium-to-long term and typically require upfront capital spend.

Delivering net zero UK – findings from a (pre-election) stocktake

A Smith School analysis published a few weeks before the 2024 general election, based on net zero technology deployment numbers across three main sectors (power, buildings, and transport) from the Climate Change Committee’s (CCC) Sixth Carbon Budget, showed that the additional annual investment needed by 2030 from UK businesses, households and government to get back on to the CCC’s ‘Balanced Net Zero’ scenario pathway was around 25% more than ‘current policies’ at the time were set to deliver.

Our analysis also looked at the savings that would accrue from the adoption of clean technologies with lower running costs compared to their fossil fuel counterparts. For instance, comparing a heat pump to a gas boiler, this meant factoring in the initial extra capital costs as well as around 15 years of lower running costs. A similar calculation was made for other technologies such as Electric Vehicles (EVs) versus petrol cars, and power generated from renewables versus fossil fuels. We also considered carbon prices (set by the UK emissions trading scheme) over that period.

Implications for net zero investments going forward

What do the new fiscal rules imply for the outlook for UK net zero investments going forward? Two ongoing/imminent changes have a bearing on our earlier conclusions: the ‘current policies’ scenario has changed since July 2024 with the introduction of new policies, and, the Seventh Carbon Budget expected in early 2025 will contain updated technology deployment numbers. Regardless, we make three broad observations based on our earlier analysis (as described above).

First, the new fiscal rules will provide the government a way of recognising the long-term value of net zero investment. Many net zero investments are considered illiquid, that is, would have counted against the old PSND constraint, but generate future savings, which the new PSNFL rules will recognise. For example, our earlier analysis had estimated that a well-coordinated net zero transition could save most households with at least one car up to £380 per year, making them better off overall. Combined with potential reforms to electricity markets, which better share the benefits of cheaper renewables with consumers, it could also mean that there are avoided costs of government intervention on shielding consumers from future energy price spikes created through volatility in international fossil fuel prices. For instance, the OBR’s estimate of the total cost of the Sunak government’s energy support package to mitigate the spike in international energy prices was £52 billion in 2022-23.

Second, a growth-enhancing strategy based on the new fiscal rules should combine investment in early technology, such as CCS, with productivity-enhancing investment in cost-saving technologies like renewables and EVs. Labour’s policy announcements have indicated a strong focus on industrial transformation and innovation. The government has announced plans to invest £22 billion over 25 years in two Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) clusters, in North England and Wales. Labour have doubled the green hydrogen target set by the previous government (despite previous targets not having been achieved), and committed in their manifesto up to £500 million on green hydrogen manufacturing. They have also committed to building 8 battery plants across the country, with £2 billion in financing support.

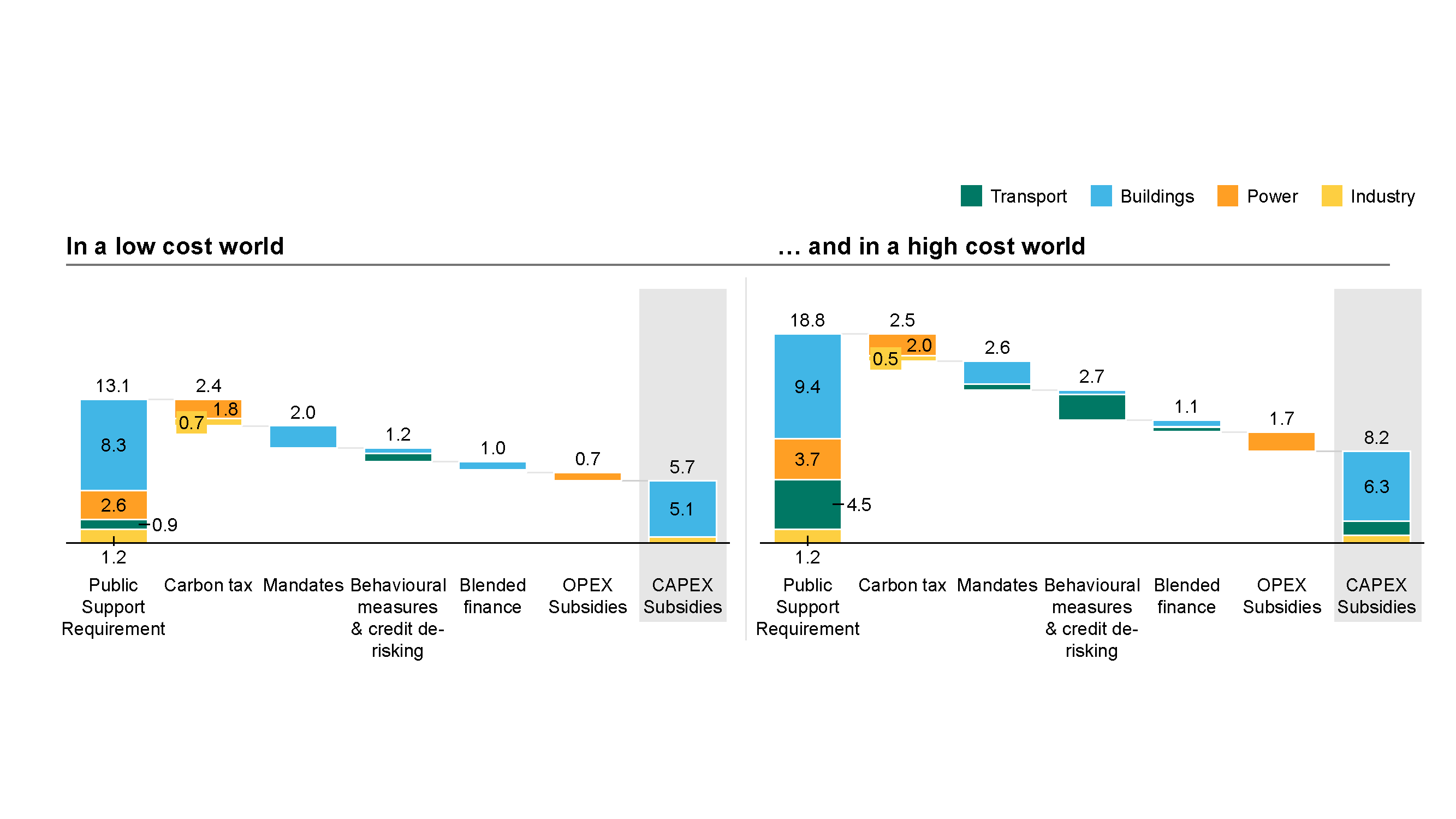

Our analysis from earlier this year assumed that the majority of industrial sector net zero investment and technology deployment occurs after 2030. While industrial decarbonisation is an important part of the picture, and could pay off politically and economically, there also exist more cost-effective and proven technologies that require investment today, including a wholesale retrofit of Britain’s aging building stock, and the scaling up of EV deployment. Our analysis showed that a balanced mix of policy measures including carbon prices, behavioural support (such as information campaigns and credit de-risking) and subsidies could ‘crowd in’ private investment to cover 50% of public sector support needed to close TCO gaps and scale up net zero technologies to the CCC’s Balanced Net Zero Pathway to 2030.

Figure 1: Effect of a ‘balanced policy mix’ on public support required for net zero

Source: Smith School Analysis, May 2024

The new fiscal rules could therefore allow Labour the rare ability to do both – making an informed investment in technologies of the future, while also making concrete progress towards net zero buildings & transport today.

Third, net zero investments fit in with other policy priorities in terms of the co-benefits they will generate. Housebuilding as a powerful case in point. The Labour government pledged to build 1.5 million new homes over its 5 years in government. If delivered alongside net zero considerations – (e.g. net zero new build standards) – it could unlock a massive opportunity to boost energy efficiency (e.g. a 50% demand reduction by 2050) and permanently reduce energy bills for households (as described above), whilst also delivering jobs in net zero industries if combined with appropriate skilling policies. Our analysis from May 2024 showed that by 2030, the investments to deliver net zero could create approximately 250,000 full-time equivalent UK jobs above those in our baseline (current policies) scenario. These include ‘direct jobs’ (i.e. 150,000) as well as ‘indirect’ jobs (i.e. 100,000) - these jobs would be the result of the construction and installation of new technologies, occurring in the year of delivery, alongside operational jobs that continue throughout the lifecycle of the investments and beyond 2030. Our analysis estimated that the additional jobs would be concentrated in the Maintenance & Repair, Financial intermediation, Transport equipment and Transportation sectors, reflecting the operational need of new technologies, and the UK’s comparative advantage in the financial sector.

In summary, the change is good news for net zero investment - the shift in rules explicitly enables more public capital investment which will be crucial to funding or catalysing funding for green infrastructure. The new fiscal rules could allow Labour the rare ability to do two things – making an informed investment in technologies of the future, while also making concrete progress towards net zero buildings and transport today.

[1] Public Sector Net Debt (PSND) = [Deposits & Currency + Bonds & Loans] – [Liquid Financial Assets]

Public Sector Net Financial Liabilities (PSNFL) = [Deposits & Currency + Bonds & Loans + Other Financial Liabilities + Funded public sector pension liabilities] – [Liquid Financial Assets + Illiquid Financial Assets]. See IFS (2023) Public sector net worth as a fiscal target Green Budget 2023 - Chapter 6 for more detail.