The air we breathe: lessons from Beijing’s airpocalypse

June 20th, Clean Air Day, an annual event to raise awareness about the importance of clean air for the environment, resonates with me. I should know: I live in a mega-city where the air pollution was once so bad, a government account tweeted it was “crazy bad”.

Source: You're not from around here

It’s 11 January, 2013, 10pm. This evening, I go see local Beijing bands at a small crowded live music venue called School Bar. 30 minutes into the show, the indoor smoking starts to irritate me and so I go outside in the hope of catching fresh air. Instead, I am immediately hit face first with a thick dark cloud of ashen metallic smelling air almost worse than indoor smoking. That evening, Beijing, China’s capital city and home to the Great Wall of China, is now enveloped in a blanket of smog so severe, air pollution levels (as measured by PM2.5 levels) are 22 times higher than World Health Organizations guidelines. Alas, this would come to be one of many occurrences that would soon earn Beijing the new dubious distinction as home to the “Airpocalypse”, and as one of the most air polluted cities on Earth.

The key culprit causing these air pollution episodes are industrial emissions from heavy industries such as coal power, steel, cement and glass manufacturing in Hebei, the heavily industrialised province that surrounds Beijing. These emissions, coupled with traffic fumes from increasingly crowded roads, cause air pollution episodes that became a regular feature in the daily life of its over twenty million inhabitants.

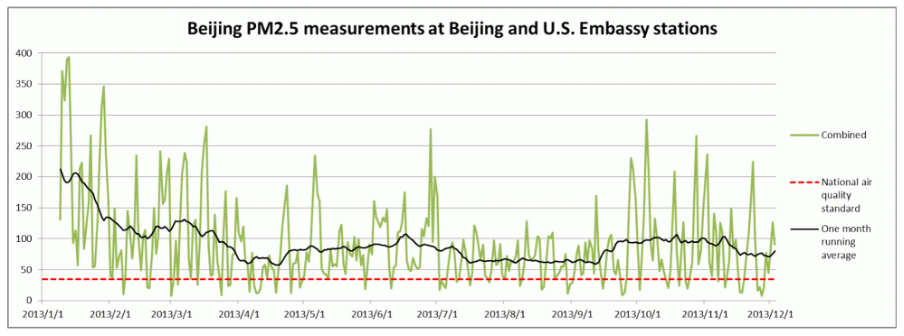

Source: Calvin Quek’s image based on official data from US embassy and Beijing stations

Throughout 2013, air pollution levels averaged 100 ug/m3, 10 times higher than the World Health Organization’s 2005 recommended level of 10ug/m3.

Some responses were incredulous, slow. Some claimed that such air pollution levels would be useful covering the case of an aerial attack on Beijing. Others claimed that it was a small price to pay for supporting China’s 8% GDP growth. Fortunately, with the advent of large screen mobile phones and access to air pollution information via phone apps, it became increasingly clear to the public and to authorities that a public health crisis was on hand.

Indeed, the lived experience of regular “airpocalypses”, where one either stayed indoors, hunkered next to air filtration machines, or braved the smog outside, wearing elaborate and uncomfortable PM2.5 air masks, was such a long drawn out ordeal to some that they ultimately left the city. My own recollection of such oppressive lifestyle restrictions is that it was on par with living during Covid-linked lockdown restrictions during 2020 – 2022.

Image: A child and her mother wearing protective face masks hold a sign protesting air pollution. Copyright: Greenpeace, Wu Di

Thankfully, by mid-year 2013, public concern about the issue had reached elevated levels, and the then new administration made solving air pollution one of its most urgent and pressing challenges, on par with fighting corruption. On 14 June 2013, China's top administrative authority, the State Council, threw the gauntlet, announcing a RMB 1.7 trillion (GBP 189 billion) plan containing 10 policy measures to deal with China's chronic air pollution crisis. Called the the "The 2013 -2017 Air Pollution Prevention Action Plan (大气污染防治行动计划2013-2017), achieving this would require intense inter-ministerial coordination between China's top economic, energy and environment agencies.

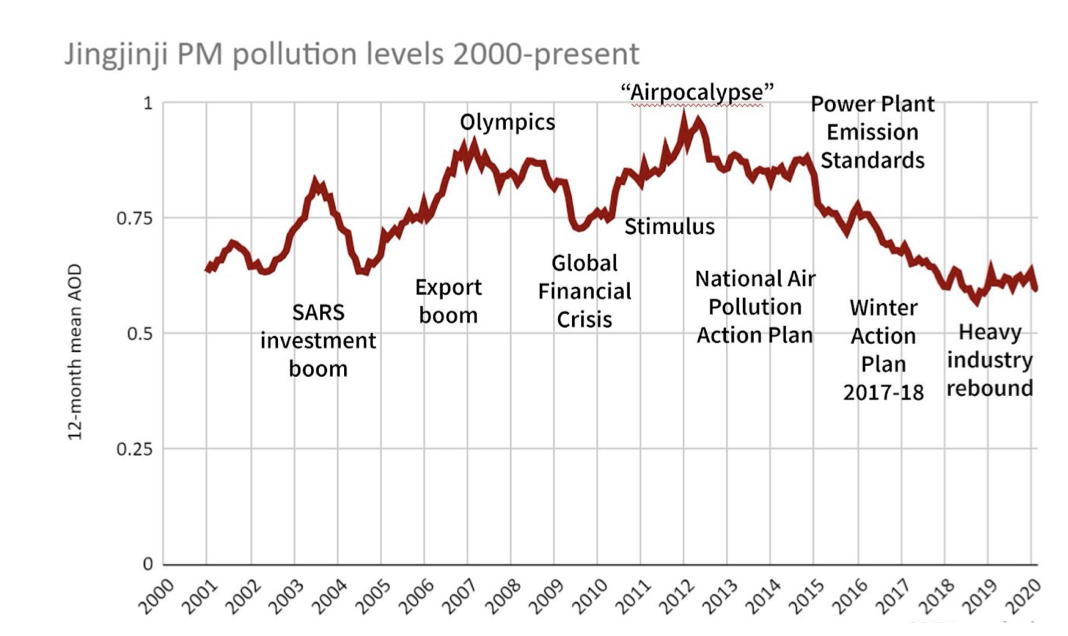

Beijing’s air pollution crisis was intimately linked to heavy industry growth, laxed environmental regulation and indeed more broadly, China’s energy intensive economic growth model, which was heavily reliant on infrastructure and fixed asset investment. While this model worked as China industrialised, such overreliance on investment as a source of economic growth ultimately led to overcapacity issues in coal power, steel, cement, chemical and other heavy industries. Simply stated, China had too much inefficient and polluting heavy industry.

Over the next few years from 2013 – 2015, the war on air pollution raged. The government went on a tear to shut down illegal coal mines, thermal power, and inefficient steel mills, install air pollution control devices at industry emission sources, invest massively in low-carbon and low pollution solar and wind power farms, and empower environmental offices throughout the greater Beijing region to enforce air pollution regulations.

The efforts paid off – average air pollution levels fell steadily from the peak of 2013 over the following years, in a remarkable turnaround.

Source: Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air

That said, Beijing’s air pollution holds lessons for policy makers globally, in the sense that much air pollution is ultimately linked to human-related factors that can be addressed and improved. Economies that rely mostly on fossil fuels for energy, transport or more broadly for economic development, have a greater risk of higher air pollution levels and harmful impacts on human health.

Air pollution is also linked to the lack of environmental standards, and for countries where agriculture is important, it is linked to seasonal land clearing and forest fires. True, some factors are beyond human control – the 1991 Mt Pinatubo eruption in the Philippines significantly raised air pollution levels. But for many other factors, for example, how and where people work and commute are human induced factors that are within our control to a degree. Ultimately, if we want blue healthy skies for ourselves and our planet, it comes down to making clear choices regarding how we go about our daily lives.

Image: Greenpeace campaign against air pollution in Beijing. Copyright: Greenpeace, Wu Di.