Give a (Hu)man a fish– a tale of potential sustainability

Give someone fish and they will eat for a day - teach them to fish and they will build fish pens - and eat the ocean away.

Growing up and going to the fish market with my grandma in Portugal, I always thought of fish being caught with fishing rods, and that piscators would only fish for the amount of catch they needed.

But fishing practices have changed dramatically since my childhood years. New materials, technologies and methods have allowed us to consume more fish than ever before. But this has come at a tremendous cost to the environment.

An unsustainable industry

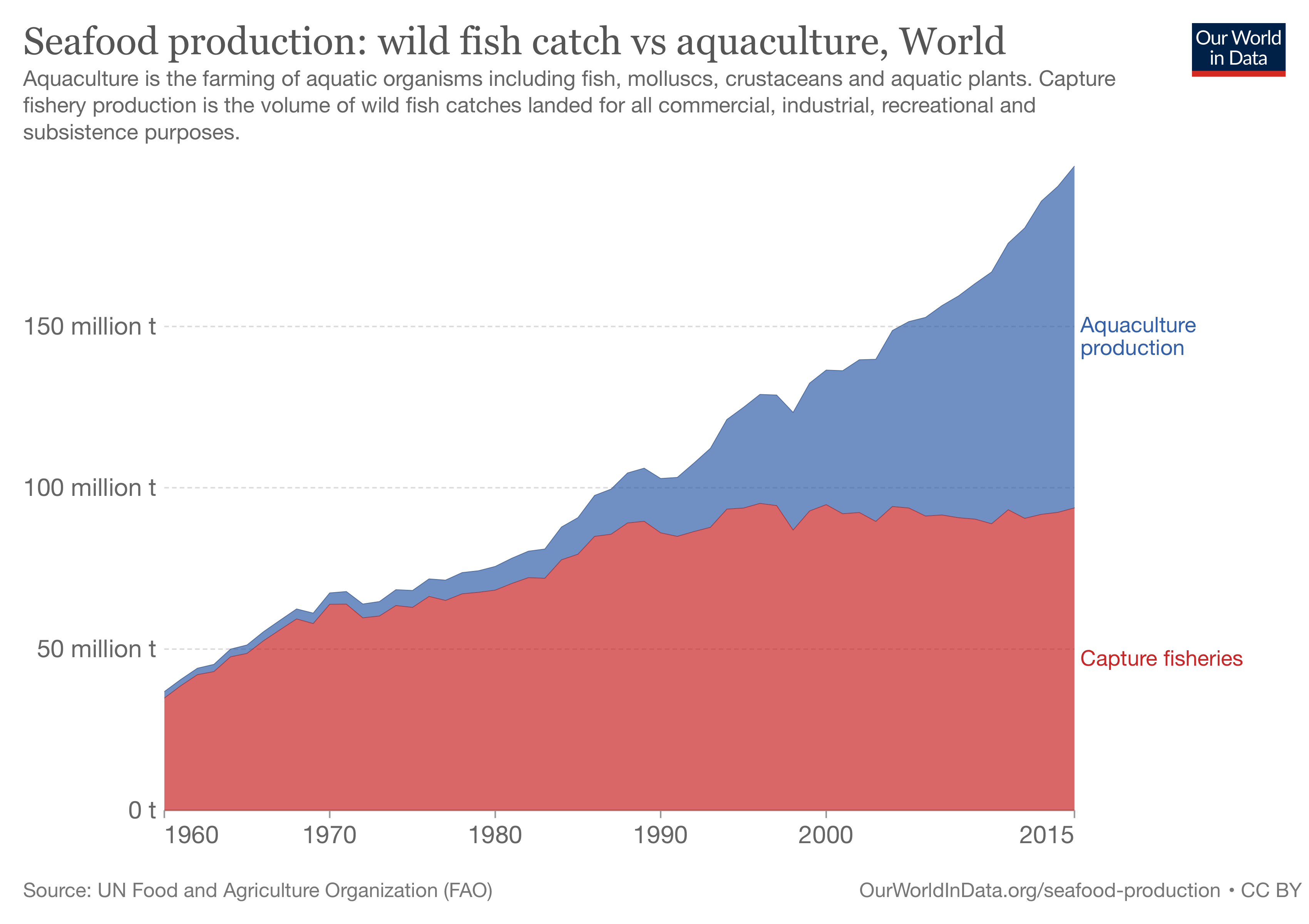

Aquaculture plays a crucial role in the global seafood supply chain. The production of farmed fish globally, has more than doubled over the last 20 years according to data from Our World in data (from circa 42 Million tonnes in 2000 to 106m tonnes in 2015). The overexploitation of wild fish stocks increased by 10% over the same period, suggesting that ‘business-as-usual’ is unsustainable, as we are not allowing enough time for the wild fish stock to replenish. And rather than landing on our plate, wild fish is being fed to farmed fish. According to research carried out in 2014, 179,000 tonnes of salmon produced in Scotland fish farms consumed 460, 000 tonnes of wild caught fish (76% of which is suitable for human consumption).

Dr Laurence Wainwright from the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment has serious concerns regarding the future of the world’s oceans

We simply cannot continue the way we are going. What we are doing is, by definition, unsustainable. Fish are a renewable resource, and if managed properly, can provide us with an infinite source of food. However, we are pushing stocks to levels beyond where they can ‘bounce back’. While aquaculture (‘fish farming) - which now accounts for over 50% of seafood production globally – plays an important role in addressing the challenge of unsustainable fishing, it too is fraught with its own set of social and environmental problems that require careful management.

A sustainable future for fishing

Studies have shown that relatively small changes in the way we consume fish could help halt the depletion of fish species and even support their replenishment in the long-term. For example, if, as in Portugal, humans in general consumed more sardines, mackerel and carp, and less salmon, seafood production could increase by as much as 6.1 tonnes.

A study by David F Miller et al (March 2022) showed that using alternatives to salmon would increase the chances of wild species to reproduce and their stocks to replenish over time. The study proposes three scenarios and in one scenario, if we ate more sardines, we would leave about 4Million tonnes of fish in the sea.

Another scenario that researchers explored was to produce carp and mussels, that don’t require wild or caught fish feed as salmon. However, carp needs to be raised in ponds and pond dredging releases carbon emissions (4,300 kg of CO2 per tonne of meat as opposed to just 127kg to produce a tonne of edible mussels), so further research is needed to address the best sustainable option.

There is reason to be cautiously optimistic,” says Dr Wainwright. “We are making progress – albeit slowly. Certification schemes like the Marine Stewardship Council and its counterpart for farmed seafood, the Aquaculture Stewardship Council have done an excellent job in terms of promoting responsible seafood production and consumption. Many of the NGOs who criticise such schemes – and sloppy journalism hit pieces under the guise of science like Seaspiracy - fail to realise that it is impossible to go from nothing to perfect. There have to be intermediary steps along the way. And while not perfect, the MSC and ASC are tremendously important.

What can we do as consumers?

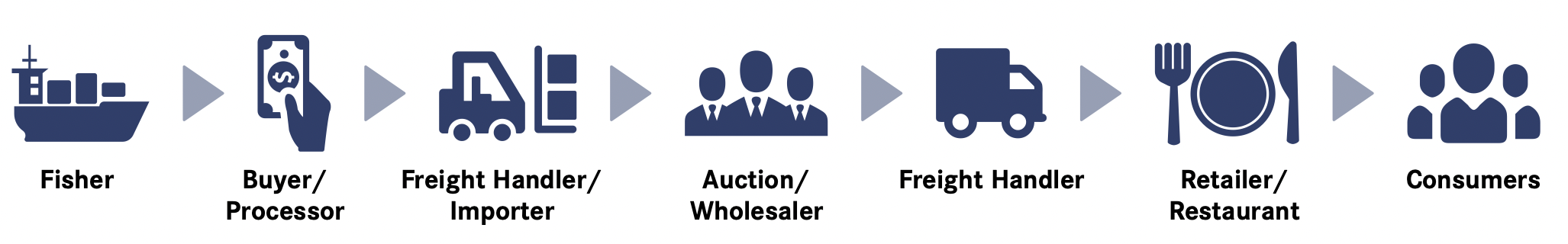

In order to make sustainable choices, it’s not enough to look at the labels anymore; we also need to look at origin, which is not always the “true” origin of the fish – some fish are packaged and cut in different countries, and like other products in a global supply chain, might traverse multiple countries before being sold on the market. For example, A report from SeaChoice focused on Canada fishing industry, shows that fish may be caught in Canada but sent as far away as China for packaging and filleting. This product would then be labelled as a product of China.

(Source: Canadians eating in the dark: a report card of international seafood labelling requirements, SeaChoice)

Dr Wainwright explains:

Over the past 50 years, forces of globalization have created a situation where supply chains of goods typically span multiple countries, with resource extraction, production, distribution, sale and consumption often taking place in different geographical locations (Meixell & Gargeya, 2005; Baldwin, 2013). Like many food products, seafood has been a part of this trend, and there is increasing disconnect and complexity involved in getting a seafood product from point of capture/farming to the place of end consumption.

However, supporting sustainability is still expensive. For UK consumers, the most expensive fish is still the one produced in the UK and until carbon price is factored in, local produce will remain expensive.

These festivals are based around eating sardines and mackerel, an essential part of our staple diet.

What next for the fishing industry?

There is room to create regulations and practices that will ensure farmed fish is fed sustainably and will retain all its benefits for humans. Companies should be encouraged to monitor the fish, see if they’re healthy and give these fish the best life they can have before we have them on a plate.

After all, we still want good, healthy, tasty food, right?

It is clear that change must happen – and quickly,” stresses Dr Wainwright. “But change is not akin to eliminating actors from the industry altogether. Fishing and seafood farming practices – done legally and based on industry best practice and voluntary adoption of high-quality certification schemes such as ASC and MSC – have a very legitimate and necessary place in the opinion of this author. Furthermore, as debates around problems such as unstainable fishing continue to become increasingly prominent (and increasingly measurable, through largescale mechanisms such as the UN SDGs), discussions will increasingly be raised around the extent to which information and or/ideology is used in attempts to meet these challenges – including the role of artefacts such as rankings, guides and lists and what role they play in making a judgement and disseminating information. It is my view that we must always strive to follow the best available scientific evidence when making decisions about environmental matters, whilst also showing a level of understanding and appreciation for actors who are not yet perfect but are making real efforts to reinvent themselves towards an orientation which is realistic about the finite resources of the world’s ecosystems and the carrying capacity and boundaries of our planet.

Fishing changed dramatically since I was a child, and fish markets are flooded with aquaculture produce.

Portuguese aquaculture occurs mainly in old salt pans in central and southern Portugal and a recent study explore the possibility of introducing fish pens along the coast with the aim to protect the ocean’s biodiversity and ease the pressure on wild fish stocks. However, these are still early days and more research is needed to consider the right structures that would withstand adverse weather conditions and environmental conditions to ensure fish reproduction and growth.

Seafood alternatives

The Smith School for Enterprise and the Environment is taking the first steps towards the future of food and alternative proteins that may be the solution for low greenhouse gas emissions and feed an ever growing global population.

This doesn’t mean we should stop eating fish. It just means we should eat less or different species of fish, so fish can continue to reproduce forever.

A prominent trend in the fishing and seafood industry which started in the 1990s and has since become widespread (especially in Northern European markets) has been the phenomenon of primary producers adopting voluntary social and environmental standards in the form of certification schemes and third-party assurance systems, resulting in the generation of so called “eco-labels”. A particular species, location and fishing or farming method is assessed by a third-party (such as the Marine Stewardship Council), and ongoing compliance to a set of standards plus a financial payment to the third-party enables fishing companies to feature these labels on their products. Wijen and Chiroleu-Assouline (2019, p. 98) define these self-regulatory standards as existing to “certify that products in a variety of sectors… contribute to more environmentally “responsible” or “sustainable” business practices” and note that the increasing prominence of these market-based tools has enabled many producers to charge a price premium for their product.”

Key references

Websites:

Other references:

- Wainwright, L. (2020) Contested legitimacy: the shrimp sustainability saga in Sweden. Repro Lorensberg Print, Göteborg, Sweden

- Aunsmo A., et al (2008) Methods for investigating patterns of mortality and quantifying cause-specific mortality in sea-farmed Atlantic salmon Salmo salar. Inter-Research Science Publisher

- Ellis T., et al (2012) Mortality and fish welfare Springer Link

- Miranda, C. D., et all (2018) Current Status of the Use of Antibiotics and the Antimicrobial Resistance in the Chilean Salmon Farms Frontiers in Microbiology

- Willer D.F. et al (2022) Maximising sustainable nutrient production from coupled fisheries-aquaculture systems PLOS sustainability and transformation

- Askew, K., (2021) Troubled waters: How high fish mortality and poor animal welfare threaten the profitability of aquaculture Food Navigator

- Jenny Weitzman (2019) Confusion at the fish counter: How to eat fish responsibly The Conversation

- Gwen Ridler (2020) Fish supply chain faces lack of consumer awareness Food Manufacture

- Roebuck K., et all (2017) Canadians Eating in the dark: A report card of international seafood labelling requirements SeaChoice.org

- Mosqueira, M et al (2022) Potential for Coastal and Offshore Aquaculture in Portugal: Insights from Physico-Chemical and Oceanographic Conditions MDPI

- Dead Loss: The high cost of poor farming practices and mortalities on salmon farms (2021) Just Economics

- AQUIMAR - Overall assessment of the Portuguese coast towards the sustainable establishment of aquaculture sites